Captain Charles Sturt encounters the Murray River January 1830

Sturt's Journey

The original naming of the Murray River was the "Hume" by Hamilton Hume on 16th November, 1824 in honour of his father. While his fellow traveller Captain William Hovell claimed to have named it in honour of his "fellow traveller, Hamilton Hume". The original sighting of the Murray River by explorers was by Hume and Thomas Boyd near where Albury now stands. Sturt however, later chose the Murray to honour Sir George Murray, Secretary of State for the Colonies in the British Government in 1830. Major Thomas Mitchell recorded the Aboriginal name of the river was "Millewah".

Charles Sturt was born in Bengal, India in 1795 and educated at Harrow, England. Sturt joined the British Army, 39th Regiment of Foot in 1813. He served at the end of the Peninsular War and in Canada. In 1827 he was posted to Sydney, where he became Military Secretary to Governor Darling. Sturt hadn't relished the idea of going to Australia, but as he became more familiar with the country he changed his mind–there were so many new and engrossing interests: the vastness of the continent's undiscovered spaces, and the spectacle of a nation in the making. Sturt stayed for twenty-six years and combined exploring with the building of Australia as a nation. He was prominent in the colonisation of South Australia and served a term as Colonial Secretary.

Where do all the rivers go?

Captain Charles Sturt's first journey to discover the length of the Murray River was in 1828. An exploratory trip as ordered by the new Governor, Sir Ralph Darling was to the north-west of Sydney. Sturt accompanied by Hume travelled along the Macquarie and discovered the Darling River in northern New South Wales. He followed the drought stricken river for 60 miles north as far as Bourke. He returned to Sydney convinced that the Darling was the main outlet for tropical rains from Queensland. His question was "did it turn to the centre of Australia or head due south to the sea?" He believed the latter.

Captain Charles Sturt's first journey to discover the length of the Murray River was in 1828. An exploratory trip as ordered by the new Governor, Sir Ralph Darling was to the north-west of Sydney. Sturt accompanied by Hume travelled along the Macquarie and discovered the Darling River in northern New South Wales. He followed the drought stricken river for 60 miles north as far as Bourke. He returned to Sydney convinced that the Darling was the main outlet for tropical rains from Queensland. His question was "did it turn to the centre of Australia or head due south to the sea?" He believed the latter.

The big question was "where did all these rivers flow to?" Hume's Murray, Goulburn; Oxley's Lachlan and Macquarie; the Bogan, and the Castlereagh. Between the Condamine in the north and the Goulburn in the south. Nobody suspected that all the intervening rivers belonged to the same riparian scheme. That great discovery was yet to be made.

The two men who solved the riddle of the rivers were Sturt, in his Murray whaleboat, and Mitchell, who made four land journeys that took him as far as the Barcoo and enabled him to link up the fragments of the rivers already discovered. What sent Sturt to the Murray was a turn of Governor Darling's interests towards the south, where the Murrumbidgee River (discovered 1821 by Charles Throsby) was beginning to assume importance in the scheme of Australian colonisation. Where did the Murrumbidgee empty itself?

The Murray Journey begins

On November 3, 1829 Sturt left Sydney to assume command of the expedition that eventually turned itself into the famous Murray River Voyage. With three bullock drays, a cart, and saddle-horses, it was a typical contemporary overlander's outfit. They also took planks for building a whaleboat. To Sturt's great disappointment Hume could not go. The position was filled by George Macleay the son of the Colonial Secretary. Macleay proved an able lieutenant, companionable and resourceful as well as a strong oarsman. The team members, soldiers and convicts also proved themselves. Sent on a tough, punishing job with no guarantee of reward, they displayed unfailing loyalty and endurance. Sturt was an ideal leader.

On November 3, 1829 Sturt left Sydney to assume command of the expedition that eventually turned itself into the famous Murray River Voyage. With three bullock drays, a cart, and saddle-horses, it was a typical contemporary overlander's outfit. They also took planks for building a whaleboat. To Sturt's great disappointment Hume could not go. The position was filled by George Macleay the son of the Colonial Secretary. Macleay proved an able lieutenant, companionable and resourceful as well as a strong oarsman. The team members, soldiers and convicts also proved themselves. Sent on a tough, punishing job with no guarantee of reward, they displayed unfailing loyalty and endurance. Sturt was an ideal leader.

The account of the journey has been constructed from Sturt's diary, published in London in 1833. Following the Murrumbidgee from Wagga to Hay was slow. "The plains were open to the horizon. Views as boundless as the ocean. No timber but here and there a stunted gum or a gloomy cypress. Neither bird nor beast inhabited these lonely regions over which the silence of the grave seemed to reign." But there were a few Aboriginals living along the river: in fact, tribes varying in number and disposition were met throughout the whole journey. There was no real trouble. Sturt was confident on his present line he would meet the Darling River. "I had no doubt," he wrote, "that ultimately I would reach the coast."

Due to difficulty of travelling by land and about 10-20 miles from the Lachlan River junction, Sturt decided to go by river. On 26th December, 1829 his team assembled (lead by Carpenter Clayton) a 25 foot whaleboat and built a log skiff for carrying stores and only two oars. The party was divided - 8 for South Australia and 6 returned overland to Goulburn Plains. The boat party departed 7 January, 1830. The crew, besides Sturt and Macleay were Harris, Hopkinson, and Frasier (soldiers), and Mulholland, Macnamee, and Clayton (convicts).

The journey was initially in parts dangerous and difficult along the Murrumbidgee. "A sudden wreck and defeat of the expedition appeared imminent." The skiff filled with water and sank. Although it was recovered, together with the casks of salted meat, fresh water mixing with the brine spoiled the meat and caused the most serious food shortage of the whole trip. The men did not like freshwater fish and waterfowl where scarce.

The Murray River

January 14, 1830 was a great day in the history of exploration: "Suddenly the Murrumbidgee took a southern direction but in its tortuous course swept round to every point of the compass with the greatest irregularity. We were carried at a fearful rate down it's gloomy and contracted banks. At 3 p.m., Hopkinson called out that we were approaching a junction, and in less than a minute afterwards we were hurried into a broad and noble river." Sturt was on the Murray, 770 miles (1,239 kilometres) from its mouth.

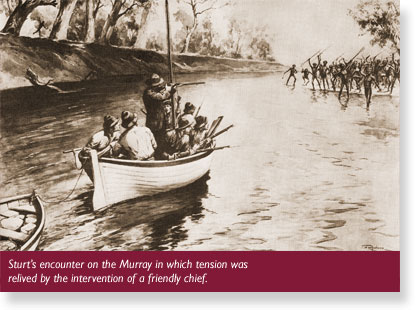

"It was impossible for me to describe the effect of so instantaneous a change of circumstances upon us. The boats were allowed to drift along at pleasure...we continued to gaze in silent admiration on the capacious channel. We had escaped from a wreck...[and] were assured of ultimate success...We were on the high road either to the south coast or to some important outlet." It was fine drifting down the sunlit river; but somewhere near the present site of Mildura, Sturt became anxious. The river's persistent north-north west trend had been puzzling. There was not sign of the Darling, no hint of a seaward change. Furthermore, he was now in the heart of Aboriginal country, and the mood of the tribes had changed. They were in war-paint and carried spears and shields. Once they swam around the boat, impeding the rowing. Sturt landed, sat down and held out a leafy branch of peace, and all was well–temporarily.

The day of 23 January, 1830 takes us to the dramatic and dangerous happenings of the Murray-Darling junction. The sail had been hoisted for the first time, and the boat was speeding when, without warning, the men saw the river shoaling fast. A huge sandbank, projecting nearly a third of the way across the channel was crowded with hostile Aboriginals. The boat ran aground. The crew were sitting shots; an engagement looked certain. "The men were given guns but instructed not to fire until I had discharged both my barrels."

The day of 23 January, 1830 takes us to the dramatic and dangerous happenings of the Murray-Darling junction. The sail had been hoisted for the first time, and the boat was speeding when, without warning, the men saw the river shoaling fast. A huge sandbank, projecting nearly a third of the way across the channel was crowded with hostile Aboriginals. The boat ran aground. The crew were sitting shots; an engagement looked certain. "The men were given guns but instructed not to fire until I had discharged both my barrels."

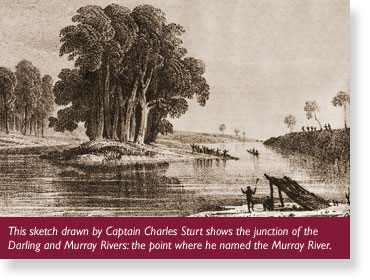

An intervening chief to which Sturt had previously held out a peace offering, swam across the stream. He was a man of authority, and he persuaded them to lower their spears. Watchful, but cool and entirely fearless, Sturt kept control of the situation. The peacemaker received a gift; guns were put away and the boat pushed off the sandbank..."Then it was just as she floated again that our attention was withdrawn to a new and beautiful stream coming from the north." It was the Darling. The explorers proceeded upstream followed on both banks by Aboriginals, curious and chattering volubly, still armed but not so ill-disposed. Macleay threw them a tin kettle as a further peace-offering.

The Darling River junction

The Darling River junction

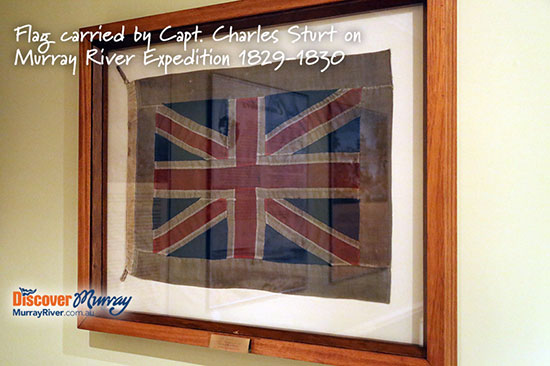

Near the present site of Wentworth, Sturt called a halt. He was now certain he was on the Darling River, no longer the dried-out disappointment he'd seen hundreds of miles away at Bourke. "I therefore directed the Union Jack to be hoisted and we all stood up in the boat and gave three distinct cheers..." Back to the junction. It was then that Sturt named the river after Sir George Murray.

Sturt's method of charting the river incorporated a sheet of paper and a compass before him, and he marked down not only the river line but also a description of the riverside country. Not a single bend was omitted. "Great heat. Seldom under 100 °F (38° C) at noon. Relays of natives still following." By the end of January they had passed what is now the border line between South Australia and Victoria. Soon afterwards the Murray played them a mean trick. It turned south, flowed past Renmark and Berri to Loxton, and then, perversely, resumed it's north-westerly direction up past Waikerie. Sturt's anxiety increased. Where were their wanderings to end?

On 3 February 1830 the old Murray made full amends: "Suddenly the river turned to the S.E. and gradually came round to E.N.E. then held on due south course." Sturt was on the Morgan Bend. There were 200 miles (321 km) to go, all due south. "The river increased in breadth and stretched away before us in magnificent reaches of from three to six miles in length. Cliffs towered above us; they were composed of a mass of shells of various kinds." Signs were beginning to suggest that the sea could not be very far off. The Murray was on a permanent course south; Aboriginals seemed to be trying to tell of some big water. Then a real harbinger of hope appeared – a seagull.

Lake Alexandrina

Lake Alexandrina

On 7 February, 1830 (near the position of Murray Bridge) an old Aboriginal distinctly informed them that they were fast approaching the sea. To the west rose some lofty ranges–the first seen since leaving the upper Murrumbidgee. The last day down the Murray was 9 February. Sturt had landed to survey the country from a piece of rising ground. Then he saw it. "Immediately below me was a beautiful lake which appeared to be a fitting reservoir for the noble stream which had led us to it. Even while grazing at this fine scene I could not but regret that the Murray had thus terminated, for I immediately foresaw that in all probability we should be disappointed in finding any practicable communication between the lake and the ocean."

Visit the Charles Sturt Museum

Tell your friends you found this at murrayriver.com.au!

Copyright Discover Murray 2026. This site or any portion of this site must not be reproduced, duplicated, copied, sold, resold, or otherwise exploited for any commercial purpose that is not expressly permitted by DISCOVER MURRAY.

Cirque Nouvelle

Cirque Nouvelle The Italian Tenors

The Italian Tenors The Australian Beach Boys Show

The Australian Beach Boys Show Song Sung Blue. The Neil Diamond Experience featuring Troy Harrison. A Story in Every Song.

Song Sung Blue. The Neil Diamond Experience featuring Troy Harrison. A Story in Every Song. Lewis Major: Triptych

Lewis Major: Triptych