Irrigation of the Murray River

Irrigation of the River Murray

Irrigation of the River Murray

The Mallee country of north western Victoria (near Mildura) was a desert. Through the Mallee along Victoria’s northern border runs the Murray, and it was the river that men’s eyes turned to for the solution of a new problem which emerged one hundred years ago. Alfred Deakin, later to become one of the founding fathers of the Commonwealth and it’s Prime Minister on three occasions, developed a conviction that the only way to settle and develop the northern part of Victoria would be by irrigation. He believed that in this region the fertile soil, the abundant sunshine and the Murray’s plentiful water, which when brought together would make even the inhospitable Mallee region prosper.

In 1884 Deakin was the Minister for Public Works and Water Supply but resigned this position to accept an appointment as President of a Royal Commission set up to examine proposals for irrigation in Victoria. In order to gain some first-hand experience of a successfully working irrigation scheme, Deakin travelled to the United States. There he met the brothers George and William Benjamin Chaffey, two Canadians who had combined their  talents to create an irrigation colony in California, which was both technically and commercially highly successful.

talents to create an irrigation colony in California, which was both technically and commercially highly successful.

Deakin was enormously impressed with what he saw, and with seemingly very little understanding of the differences between the American and Australian situations assumed that irrigation on the Chaffey scheme could be successfully transplanted to the Mallee. He pressed the Chaffeys to come to Australia and offered his full support to help them become established.

In 1886 George Chaffey arrived in Melbourne and commenced a series of frustrating negotiations with the Victorian Government. In spite of Deakin’s advocacy many local politicians were suspicious of Chaffey’s new ideas. George had reached a state of such frustration that he was at the point of returning to California when he decided to get away from Melbourne and at least travel along the Murray to the Mallee country. He reached the site of the old Mildura Station described by a Melbourne newspaper as a ‘Sahara of hissing hot winds and red driving sand, a carrion-polluted wilderness’, George Chaffey knew suddenly that he had found what he had come to Australia for. Mildura Station was a lonely and depressed place, but next to a homestead was a small and flourishing fruit and vegetable garden watered by a windmill-operated pump from the river. It was a miniscule oasis in that desert and his prophetic words were “Some day the whole of Mildura will be as this garden”.

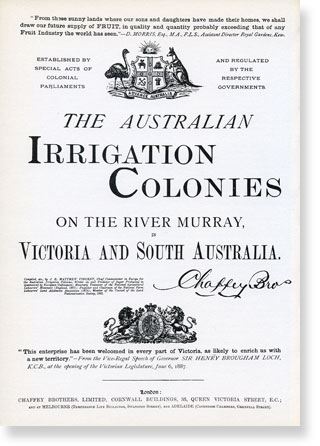

Chaffey believed that he found the conditions which would enable the development in Australia of an irrigated fruit colony based upon his successful Californian model. The brothers sold up their assets in the United States and launched the ‘Chaffey irrigation fruit colony’. In spite of the suspicion and opposition shown by some members of the Victorian parliament there was wide public and press support for the Chaffey proposal. The debate was carefully observed from across the borders by the neighbouring colonies in South Australia and New South Wales, the Chaffeys were invited by the South Australian Government to establish their fruit colony. The brothers quickly accepted and on the 14 February 1887 an agreement was signed for the establishment at Renmark in South Australia the first irrigation settlement in Australia.

The agreement reached with the South Australian Government seemed to enhance the reputation of the Chaffeys in Victoria and shortly after, on 31 May 1887 an agreement was signed between the Chaffey brothers and the Victorian Government. In August the Chaffeys arrived at Mildura Station and formally took over the land for their irrigation settlement. It seems quite clear from the recordings of the day that the River Murray itself was taken for granted; there was no thought given to the likely effects of the irrigation proposals on the river or its health, except for the possible effect on those living downstream from the water diversion. As in most cases ‘downstream’ meant South Australia, and that was a separate Colony and not of great concern to Victoria and New South Wales.

The agreement reached with the South Australian Government seemed to enhance the reputation of the Chaffeys in Victoria and shortly after, on 31 May 1887 an agreement was signed between the Chaffey brothers and the Victorian Government. In August the Chaffeys arrived at Mildura Station and formally took over the land for their irrigation settlement. It seems quite clear from the recordings of the day that the River Murray itself was taken for granted; there was no thought given to the likely effects of the irrigation proposals on the river or its health, except for the possible effect on those living downstream from the water diversion. As in most cases ‘downstream’ meant South Australia, and that was a separate Colony and not of great concern to Victoria and New South Wales.

It’s been noted interestingly that no effective analysis of the proposed irrigation scheme was researched and the differences between Australia and the other countries of the world where irrigation farming had been practised successfully. Problems encountered by the earlier irrigation colonies included publicity, finance, power and sovereignty of the individual colonies, and mechanical problems concerned with raising of water from the river and it’s transmission to where it was needed.

For the backbone of the scheme, it was envisaged that settlers with some capital would come and buy the irrigated blocks as they were developed, and the capital flow would enable the engineering works to be expanded and more land opened up. The settlers were enticed largely through The Red Book (The Australian Irrigation Colonies, Illustrated) which the Chaffeys produced. Even today The Red Book makes a magnificent read with its grand vision for a new life at Mildura. Many settlers sold up and came on the long journey from the British Isles to the heat, flies and dust storms of Mildura all fired up with the ambition of making Mildura “The Fruit Garden of the Universe”.

George Chaffey, the engineer, was laying out the channels which would carry the water (by gravity) to where it was needed and arranging for the pumps which would raise it from the river up to the channels. George eventually designed and wrote the specifications for the massive pumps which were to be the heart of the two major pumping stations needed, and ordered them from a British engineering firm. When the pumps arrived they performed magnificently year in and year out at Mildura.

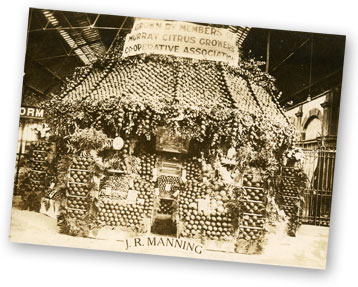

The early days provided high hopes, generous early harvests, rapidly increasing land values, and a general fever of excitement despite the difficult conditions. Such difficulties included issues over water rights, destruction of irrigations channels from the yabby and the first signs of salinity encountered in irrigation. Only six years after the Chaffey’s arrived, Mildura celebrated its first general harvest, and growers and purchasers celebrated the high quality of fruit and vegetables. Vine pests were a major problem throughout the world at this time. Phylloxera, the dreaded disease caused by a tiny, sap-sucking insect which had first appeared in France quickly spread through the regions of the world, including an appearance Geelong and in Victoria’s north-east, Rutherglen and Corowa.

The vines of Mildura and South Australia remained Phylloxera free and remain so today due to strict quarantine measures and protection by the Mallee country surrounding them. The other difficulty Mildura faced was it’s geographical location, which was independent from the rest of the country. In May 1893 the land boom was over and the great bank crash shook the economic and social structure of Victoria to its foundations. This significantly impacted the hope of Mildura and the promise of railway support was withdrawn. Mildura’s values dropped, settlers walked off the land, mortgages were foreclosed.

The early setbacks were part of irrigation pioneering and demonstrated even more forcibly in efforts to establish Murray-side settlements on communal lines. Swept along in the early enthusiasm for the changes being wrought at Mildura and Renmark, some utopian groups had sought land rights on the great river, and in 1894 the South Australian Government responded by approving and setting up ten small-scale irrigation settlements, each with control of its affairs entirely in the hands of its members. The groups were to settle at about 30km intervals – nine down-river from Renmark, the tenth up river – with about 350 men, women and children in each group. The areas chosen were Lyrup, Pyap, New Residence, Moorook, Kingston-on-Murray, Holder, Waikerie, Ramco, Gillen and New Era. Communal ways produced their own problems; those who talked most did least work and by 1896 wiser men had left. Years later, after they had been reconstituted on more normal lines, the surviving settlements prospered.

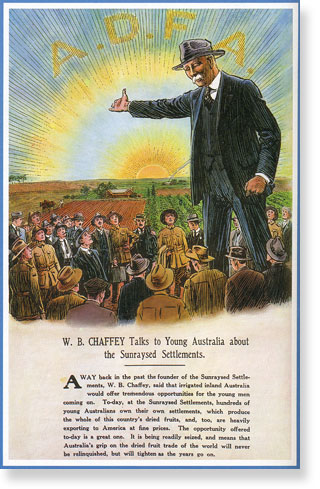

By December 1895 the Chaffey brothers’ Company had gone into liquidation and it seemed the dream was gone. George Chaffey decided to return to the United States while W.B. Chaffey stayed on in Mildura and over a period of years fought back to help overcome many of the problems which crippled the early settlement. A Royal Commission was established to investigate the failures of the irrigation schemes. In the report issued in 1896 it found that the schemes had been built on wishful thinking rather than realistic costs estimates, and that as constituted they could never operate profitably

Discover: Renmark | Paringa | Mildura | Riverland

Of related interest: Chaffey Trail Mildura | Murray River Dams, Weirs and Locks | Olivewood in Renmark

Tell your friends you found this at murrayriver.com.au!

Copyright Discover Murray 2026. This site or any portion of this site must not be reproduced, duplicated, copied, sold, resold, or otherwise exploited for any commercial purpose that is not expressly permitted by DISCOVER MURRAY.

Song Sung Blue. The Neil Diamond Experience featuring Troy Harrison. A Story in Every Song.

Song Sung Blue. The Neil Diamond Experience featuring Troy Harrison. A Story in Every Song. The Australian Beach Boys Show

The Australian Beach Boys Show Kevin Bloody Wilson Aussie Icon Tour with special guest Jenny Talia

Kevin Bloody Wilson Aussie Icon Tour with special guest Jenny Talia The Italian Tenors

The Italian Tenors Lewis Major: Triptych

Lewis Major: Triptych